Jagged, ragged, Awkward Arrays

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How do I cut particles, rather than events?

How do I compute quantities on combinations of particles?

Objectives

Learn how to slice and perform computations on irregularly shaped arrays.

Apply these skills to improve the dimuon mass spectrum.

What is Awkward Array?

The previous lesson included a tricky slice:

cut = muons["nMuon"] == 2

pt0 = muons["Muon_pt", cut, 0]

The three parts of muons["Muon_pt", cut, 0] slice

- selects the

"Muon_pt"field of all records in the array, - applies

cut, a boolean array, to select only events with two muons, - selects the first (

0) muon from each of those pairs. Similarly for the second (1) muons.

NumPy would not be able to perform such a slice, or even represent an array of variable-length lists without resorting to arrays of objects.

import numpy as np

# generates a ValueError

np.array([[0.0, 1.1, 2.2], [], [3.3, 4.4], [5.5], [6.6, 7.7, 8.8, 9.9]])

Awkward Array is intended to fill this gap:

import awkward as ak

ak.Array([[0.0, 1.1, 2.2], [], [3.3, 4.4], [5.5], [6.6, 7.7, 8.8, 9.9]])

Arrays like this are sometimes called “jagged arrays” and sometimes “ragged arrays.”

Slicing in Awkward Array

Basic slices are a generalization of NumPy’s—what NumPy would do if it had variable-length lists.

array = ak.Array([[0.0, 1.1, 2.2], [], [3.3, 4.4], [5.5], [6.6, 7.7, 8.8, 9.9]])

array.tolist()

array[2]

array[-1, 1]

array[2:, 0]

array[2:, 1:]

array[:, 0]

Quick quiz: why does the last one raise an error?

Boolean and integer slices work, too:

array[[True, False, True, False, True]]

array[[2, 3, 3, 1]]

Like NumPy, boolean arrays for slices can be computed, and functions like ak.num are helpful for that.

ak.num(array)

ak.num(array) > 0

array[ak.num(array) > 0, 0]

array[ak.num(array) > 1, 1]

Now consider this (similar to an example from the first lesson):

cut = array * 10 % 2 == 0

array[cut]

This array, cut, is not just an array of booleans. It’s a jagged array of booleans. All of its nested lists fit into array’s nested lists, so it can deeply select numbers, rather than selecting lists.

Application: selecting particles, rather than events

Returning to the big TTree from the previous lesson,

import uproot

file = uproot.open(

"root://eospublic.cern.ch//eos/opendata/cms/derived-data/AOD2NanoAODOutreachTool/Run2012BC_DoubleMuParked_Muons.root"

)

tree = file["Events"]

muon_pt = tree["Muon_pt"].array(entry_stop=10)

This jagged array of booleans selects all muons with at least 20 GeV:

particle_cut = muon_pt > 20

muon_pt[particle_cut]

and this non-jagged array of booleans (made with ak.any) selects all events that have a muon with at least 20 GeV:

event_cut = ak.any(muon_pt > 20, axis=1)

muon_pt[event_cut]

Quick quiz: construct exactly the same event_cut using ak.max.

Quick quiz: apply both cuts; that is, select muons with over 20 GeV from events that have them.

Hint: you’ll want to make a

cleaned = muon_pt[particle_cut]

intermediary and you can’t use the variable event_cut, as-is.

Hint: the final result should be a jagged array, just like muon_pt, but with fewer lists and fewer items in those lists.

Solution (no peeking!)

cleaned = muon_pt[particle_cut] final_result = cleaned[event_cut] final_result.tolist() [[32.911224365234375, 23.72175407409668], [57.6067008972168, 53.04507827758789], [23.906352996826172]]

Combinatorics in Awkward Array

Variable-length lists present more problems than just slicing and computing formulas array-at-a-time. Often, we want to combine particles in all possible pairs (within each event) to look for decay chains.

Pairs from two arrays, pairs from a single array

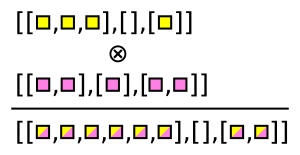

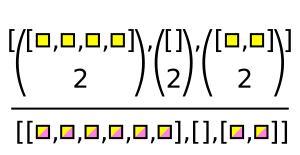

Awkward Array has functions that generate these combinations. For instance, ak.cartesian takes a Cartesian product per event (when axis=1, the default).

numbers = ak.Array([[1, 2, 3], [], [5, 7], [11]])

letters = ak.Array([["a", "b"], ["c"], ["d"], ["e", "f"]])

pairs = ak.cartesian((numbers, letters))

These pairs are 2-tuples, which are like records in how they’re sliced out of an array: using strings.

pairs["0"]

pairs["1"]

There’s also ak.unzip, which extracts every field into a separate array (opposite of ak.zip).

lefts, rights = ak.unzip(pairs)

lefts

rights

Note that these lefts and rights are not the original numbers and letters: they have been duplicated and have the same shape.

The Cartesian product is equivalent to this C++ for loop over two collections:

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.size(); i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < letters.size(); j++) {

// compute formula with numbers[i] and letters[j]

}

}

Sometimes, though, we want to find all pairs within a single collection, without repetition. That would be equivalent to this C++ for loop:

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.size(); i++) {

for (int j = i + 1; i < numbers.size(); j++) {

// compute formula with numbers[i] and numbers[j]

}

}

The Awkward function for this case is ak.combinations.

pairs = ak.combinations(numbers, 2)

pairs

lefts, rights = ak.unzip(pairs)

lefts * rights # they line up, so we can compute formulas

Application to dimuons

The dimuon search in the previous lesson was a little naive in that we required exactly two muons to exist in every event and only computed the mass of that combination. If a third muon were present because it’s a complex electroweak decay or because something was mismeasured, we would be blind to the other two muons. They might be real dimuons.

A better procedure would be to look for all pairs of muons in an event and apply some criteria for selecting them.

In this example, we’ll ak.zip the muon variables together into records.

import uproot

import awkward as ak

file = uproot.open(

"root://eospublic.cern.ch//eos/opendata/cms/derived-data/AOD2NanoAODOutreachTool/Run2012BC_DoubleMuParked_Muons.root"

)

tree = file["Events"]

arrays = tree.arrays(filter_name="/Muon_(pt|eta|phi|charge)/", entry_stop=10000)

muons = ak.zip(

{

"pt": arrays["Muon_pt"],

"eta": arrays["Muon_eta"],

"phi": arrays["Muon_phi"],

"charge": arrays["Muon_charge"],

}

)

arrays.type

muons.type

The difference between arrays and muons is that arrays contains separate lists of "Muon_pt", "Muon_eta", "Muon_phi", "Muon_charge", while muons contains lists of records with "pt", "eta", "phi", "charge" fields.

Now we can compute pairs of muon objects

pairs = ak.combinations(muons, 2)

pairs.type

and separate them into arrays of the first muon and the second muon in each pair.

mu1, mu2 = ak.unzip(pairs)

Quick quiz: how would you ensure that all lists of records in mu1 and mu2 have the same lengths? Hint: see ak.num and ak.all.

Since they do have the same lengths, we can use them in a formula.

import numpy as np

mass = np.sqrt(

2 * mu1.pt * mu2.pt * (np.cosh(mu1.eta - mu2.eta) - np.cos(mu1.phi - mu2.phi))

)

Quick quiz: how many masses do we have in each event? How does this compare with muons, mu1, and mu2?

Plotting the jagged array

Since this mass is a jagged array, it can’t be directly histogrammed. Histograms take a set of numbers as inputs, but this array contains lists.

Supposing you just want to plot the numbers from the lists, you can use ak.flatten to flatten one level of list or ak.ravel to flatten all levels.

import hist

hist.Hist(hist.axis.Regular(120, 0, 120, label="mass [GeV]")).fill(

ak.ravel(mass)

).plot()

Alternatively, suppose you want to plot the maximum mass-candidate in each event, biasing it toward Z bosons? ak.max is a different function that picks one element from each list, when used with axis=1.

ak.max(mass, axis=1)

Some values are None because there is no maximum of an empty list. ak.flatten/ak.ravel remove missing values (None) as well as squashing lists,

ak.flatten(ak.max(mass, axis=1), axis=0)

but so does removing the empty lists in the first place.

ak.max(mass[ak.num(mass) > 0], axis=1)

Exercise: select pairs of muons with opposite charges

This is neither an event-level cut nor a particle-level cut, it is a cut on particle pairs.

Solution (no peeking!)

The

mu1andmu2variables are the left and right halves of muon pairs. Therefore,cut = (mu1.charge != mu2.charge)has the right multiplicity to be applied to the

massarray.hist.Hist(hist.axis.Regular(120, 0, 120, label="mass [GeV]")).fill( ak.ravel(mass[cut]) ).plot()plots the cleaned muon pairs.

Exercise (harder): plot the one mass candidate per event that is strictly closest to the Z mass

Instead of just taking the maximum mass in each event, find the one with the minimum difference between computed mass and

zmass = 91.Hint: use ak.argmin with

keepdims=True.Anticipating one of the future lessons, you could get a more accurate mass by asking the Particle library:

import particle, hepunits zmass = particle.Particle.findall("Z0")[0].mass / hepunits.GeVSolution (no peeking!)

Instead of maximizing

mass, we want to minimizeabs(mass - zmass)and apply that choice tomass. ak.argmin returns the index position of this minimum difference, which we can then apply to the originalmass. However, withoutkeepdims=True, ak.argmin removes the dimension we would need for this array to have the same nested shape asmass. Therefore, wekeepdims=Trueand then use ak.ravel to get rid of missing values and flatten lists.The last step would require two applications of ak.flatten: one for squashing lists at the first level and another for removing

Noneat the second level.which = ak.argmin(abs(mass - zmass), axis=1, keepdims=True) hist.Hist(hist.axis.Regular(120, 0, 120, label="mass [GeV]")).fill( ak.ravel(mass[which]) ).plot()

Key Points

NumPy (and almost all array libraries) is only for rectilinear collections of numbers: arrays, tables, and tensors.

Awkward Array extends NumPy’s slicing and array-manipulation to jagged arrays and more general data types (such as nested records).

These extensions are useful for physics.

There’s usually more than one way to get what you want.