Basic file I/O with Uproot

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I find my data in a ROOT file?

How can I plot it?

How can I write new data to a ROOT file?

Objectives

Learn how to navigate through a ROOT file.

Learn how to send ROOT data to the libraries that can act on them.

Learn how to write histograms and TTrees to files.

What is Uproot?

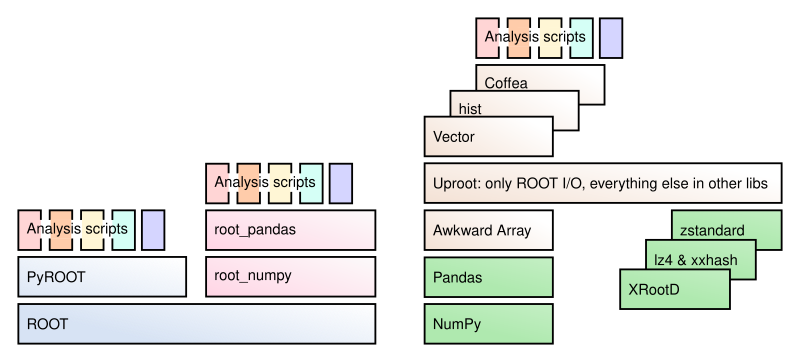

Uproot is a Python package that reads and writes ROOT files and is only concerned with reading and writing (no analysis, no plotting, etc.). It interacts with NumPy, Awkward Array, and Pandas for computations, boost-histogram/hist for histogram manipulation and plotting, Vector for Lorentz vector functions and transformations, Coffea for scale-up, etc.

Uproot is implemented using only Python and Python libraries. It doesn’t have a compiled part or require a specific version of ROOT. (This means that if you do use ROOT for something other than I/O, your choice of ROOT version is not constrained by I/O.)

As a consequence of being an independent implementation of ROOT I/O, Uproot might not be able to read/write certain data types. Which data types are not implemented is a moving target, as new ones are always being added. A good approach for reading data is to just try it and see if Uproot complains. For writing, see the lists of supported types in the Uproot documentation (blue boxes in the text).

Reading data from a file

Opening the file

To open a file for reading, pass the name of the file to uproot.open. In scripts, it is good practice to use Python’s with statement to close the file when you’re done, but if you’re working interactively, you can use a direct assignment.

import skhep_testdata

filename = skhep_testdata.data_path(

"uproot-Event.root"

) # downloads this test file and gets a local path to it

import uproot

file = uproot.open(filename)

To access a remote file via HTTP or XRootD, use a "http://...", "https://...", or "root://..." URL. If the Python interface to XRootD is not installed, the error message will explain how to install it.

Listing contents

This “file” object actually represents a directory, and the named objects in that directory are accessible with a dict-like interface. Thus, keys, values, and items return the key names and/or read the data. If you want to just list the objects without reading, use keys. (This is like ROOT’s ls(), except that you get a Python list.)

file.keys()

Often, you want to know the type of each object as well, so uproot.ReadOnlyDirectory objects also have a classnames method, which returns a dict of object names to class names (without reading them).

file.classnames()

Reading a histogram

If you’re familiar with ROOT, TH1F would be recognizable as histograms and TTree would be recognizable as a dataset. To read one of the histograms, put its name in square brackets:

h = file["hstat"]

h

Uproot doesn’t do any plotting or histogram manipulation, so the most useful methods of h begin with “to”: to_boost (boost-histogram), to_hist (hist), to_numpy (NumPy’s 2-tuple of contents and edges), to_pyroot (PyROOT), etc.

h.to_hist().plot()

Uproot histograms also satisfy the UHI plotting protocol, so they have methods like values (bin contents), variances (errors squared), and axes.

h.values()

h.variances()

list(h.axes[0]) # "x", "y", "z" or 0, 1, 2

Reading a TTree

A TTree represents a potentially large dataset. Getting it from the uproot.ReadOnlyDirectory only returns its TBranch names and types. The show method is a convenient way to list its contents:

t = file["T"]

t.show()

Be aware that you can get the same information from keys (an uproot.TTree is dict-like), typename, and interpretation.

t.keys()

t["event/fNtrack"]

t["event/fNtrack"].typename

t["event/fNtrack"].interpretation

(If an uproot.TBranch has no interpretation, it can’t be read by Uproot.)

The most direct way to read data from an uproot.TBranch is by calling its array method.

t["event/fNtrack"].array()

We’ll consider other methods in the next lesson.

Reading a… what is that?

This file also contains an instance of type TProcessID. These aren’t typically useful in data analysis, but Uproot manages to read it anyway because it follows certain conventions (it has “class streamers”). It’s presented as a generic object with an all_members property for its data members (through all superclasses).

file["ProcessID0"]

file["ProcessID0"].all_members

Here’s a more useful example of that: a supernova search with the IceCube experiment has custom classes for its data, which Uproot reads and represents as objects with all_members.

icecube = uproot.open(skhep_testdata.data_path("uproot-issue283.root"))

icecube.classnames()

icecube["config/detector"].all_members

icecube["config/detector"].all_members["ChannelIDMap"]

Writing data to a file

Uproot’s ability to write data is more limited than its ability to read data, but some useful cases are possible.

Opening files for writing

First of all, a file must be opened for writing, either by creating a completely new file or updating an existing one.

output1 = uproot.recreate("completely-new-file.root")

output2 = uproot.update("existing-file.root")

(Uproot cannot write over a network; output files must be local.)

Writing strings and histograms

These uproot.WritableDirectory objects have a dict-like interface: you can put data in them by assigning to square brackets.

output1["some_string"] = "This will be a TObjString."

output1["some_histogram"] = file["hstat"]

import numpy as np

output1["nested_directory/another_histogram"] = np.histogram(

np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)

)

In ROOT, the name of an object is a property of the object, but in Uproot, it’s a key in the TDirectory that holds the object, so that’s why the name is on the left-hand side of the assignment, in square brackets. Only the data types listed in the blue box in the documentation are supported: mostly just histograms.

Writing TTrees

TTrees are potentially large and might not fit in memory. Generally, you’ll need to write them in batches.

One way to do this is to assign the first batch and extend it with subsequent batches:

import numpy as np

output1["tree1"] = {

"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000),

"y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000),

}

output1["tree1"].extend(

{"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000), "y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)}

)

output1["tree1"].extend(

{"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000), "y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)}

)

another is to create an empty TTree with uproot.WritableDirectory.mktree, so that every write is an extension.

output1.mktree("tree2", {"x": np.int32, "y": np.float64})

output1["tree2"].extend(

{"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000), "y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)}

)

output1["tree2"].extend(

{"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000), "y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)}

)

output1["tree2"].extend(

{"x": np.random.randint(0, 10, 1000000), "y": np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000000)}

)

Performance tips are given in the next lesson, but in general, it pays to write few large batches, rather than many small batches.

The only data types that can be assigned or passed to extend are listed in the blue box in this documentation. This includes jagged arrays (described in the lesson after next), but not more complex types.

Reading and writing RNTuples

TTree has been the default format to store large datasets in ROOT files for decades. However, it has slowly become outdated and are not optimized for modern systems. This is where the RNTuple format comes in. It is a modern serialization format that is designed with modern systems in mind and is planned to replace TTree in the coming years. Version 1.0.0.0 is out and will be supported “forever”.

RNTuples are much simpler than TTrees by design, and this time there is an official specification, which makes it much easier for third-party I/O packages like Uproot to support. Uproot already supports reading the full RNTuple specification, meaning that you can read any RNTuple you find in the wild. It also supports writing a large part of the specification, and intends to support as much as it makes sense for data analysis.

To ease the transition into RNTuples, we are designing the interface to match the one for TTrees as closely as possible. Let’s look at a simple example for reading and writing RNTuples.

Again, we’ll use a sample file from the

filename = skhep_testdata.data_path("ntpl001_staff_rntuple_v1-0-0-0.root")

file = uproot.open(filename)

This time, if we print the class names, we see that there is an RNTuple instead of a TTree.

file.classnames()

Then to read the data from the RNTuple works in an analogous way.

rntuple = file["Staff"]

data = rntuple.arrays()

Writing again works in a very similar way to TTrees. However, since TTrees are still the default format used in more places, writing something like file[key] = data will default to writing the data as a TTree. When we want to write an RNTuple, we need to specifically tell Uproot that we want to do so. For now, we need to use an Awkward Array (which will be covered in a later lesson) to specify the data, but the interface will be extended to match TTrees.

import awkward as ak

data = ak.Array({"my_int_data": [1, 2, 3], "my_float_data": [1.0, 2.0, 3.0]})

more_data = ak.Array({"my_int_data": [4, 5, 6], "my_float_data": [4.0, 5.0, 6.0]})

output3 = uproot.recreate("new-file-with-rntuple.root")

rntuple = output3.mkrntuple("my_rntuple", data)

rntuple.extend(more_data)

For the rest of the tutorial we will stick to using TTrees since this is still the main data format that you’ll encounter for now.

Key Points

Uproot TDirectories and TTrees have a dict-like interface.

Uproot reading methods are primarily intended to get data into a more specialized library.

Uproot writing is more limited, but it can write histograms and TTrees.